“Dogs have more genetic diseases than any other species on the planet.” David Ishee told me this early in our conversation. His claim makes sense: there’s no other animal that humans have purposefully bred with an emphasis on form over function–aesthetics over health–for so long.

Centuries of inbreeding have left many dog breeds with a severely limited gene pool, and this lack of genetic diversity is to blame for disorders like brachycephaly in bulldogs, hyperuricemia in dalmations, and cardiomyopathy in boxers.

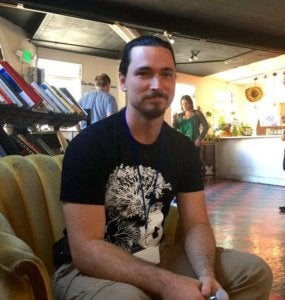

Ishee is a breeder from rural Mississippi who’s on a mission to change all this.

Up until now, he’s been using selective breeding to do so. His first big project involved mastiffs, which were once considered a warrior breed, but devolved into the docile, lazy pets we see today. “They lost their health, their drive and their athleticism,” Ishee said. “My project as a breeder is to bring all that back to them.”

He envisioned an ideal mastiff: 150-170 pounds, 30+ inches at the shoulders, tight-skinned, dry-mouthed, and free of inherited health problems. Eight years later, this super-mastiff (which is really just a return to what nature intended a mastiff to be) has become a reality.

Ishee has plans to expand his health-focused breeding to other dogs, but he wants a better tool to do so.

Enter gene editing.

Gene editing for everyone

You’d think that to tweak the genome of an animal, some serious training and education would be necessary–maybe a post-graduate biology degree or several years working in the lab of a large genetics company.

But in a prime example of both the democratization and demonetization of technology, Ishee taught himself to do genetic engineering right in his own backyard shed, using a kit and some DNA he ordered online.

“I think every dog breeder wants better tools than just breeding. But everybody assumes it’s impossible, or crazy expensive, so I never considered actually trying,” Ishee said. That changed after he saw a TED talk about genetic engineering, namely because of the ease and low cost of ordering custom synthesized DNA.

He continued, “The biggest thing here is the collapsing price of DNA sequencing and synthesis. You can order synthetic DNA for about nine cents a base pair. When I ordered my construct a year and a half ago, I paid 23 cents a base pair. Six years before that it would’ve been $1.30 a base pair. When it gets down to pennies, people will be able to do much more complex things.”

It’s this very idea, though–of anyone being able to do complex gene editing at home with supplies ordered online–that’s caused a tightening of regulations, most recently from the FDA.

Regulatory crackdown

As of mid-January, the FDA updated its guidance for animals produced using genome editing to classify the edited portion of the animal’s genome as a veterinary drug. This means the animals themselves are subject to the same regulations as new animal drugs.

While acknowledging that genome editing technology could have “potentially profound beneficial effects on human and animal health,” the FDA statement also mentions possible unwanted impacts on the environment and ecosystem, as well as on individual genomes.

The Retail Giant Walmart Introduces Walmart + And Why We Are Poised To See $1000

The new guidelines threw a wrench into Ishee’s next project: to use gene editing to rid dalmations of hyperuricemia. A mutation on the dogs’ SLC2A9 gene leads to excess uric acid in the blood, which causes painful bladder stones to form and can even cause the bladder to burst.

To breed out this mutation, a breeder would have to wait for a positive mutation to randomly appear–and since it’s a closed and inbred population, that could take decades. CRISPR gene editing could do it in months.

Besides a series of complex approvals and permissions, though, the FDA regulations also involve hefty fees, reaching into six figures per animal. It’s a sum that’s feasible for a large corporation, but not so much for a breeder. No large corporation is likely to take on projects similar to Ishee’s, because there’s not much money to be made. If pet owners are happy–or unaware–as is, why invest in creating healthier dogs?

Designer dogs, designer humans?

The FDA guidance points out that gene editing “has raised fundamental ethical questions about human and animal life.” It’s these questions that are at the root of the knee-jerk negative reaction many have when it comes to these topics. If we allow gene editing to cure diseases in dogs, will a slippery slope ensue? Will I be able to custom-design my pet in the future, and if yes, is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Perhaps most significantly, if breeders like Ishee can prove that CRISPR is an easy way to rid dogs of health issues, will that pave the way for the technology to be more widely used on humans? Scientists in China produced gene-edited beagles in 2015, with one scientist saying their research had biomedical ends, as “Dogs are very close to humans in terms of metabolic, physiological, and anatomical characteristics.”

In Ishee’s opinion, genetic engineering and selective breeding aren’t all that different. “CRISPR doesn’t allow us to do anything we couldn’t do before. It’s just a bit easier, cheaper and faster,” he said. “Breeding gives you a lot less control and fewer degrees of freedom. But as far as the ethics is concerned, you’re doing the exact same thing.”

Old bricks build an old house

Speaking of ethics–if humans caused dogs to have all these health problems in the first place, and now we have the technology to fix those problems, don’t we have a moral obligation to do so?

English bulldogs are riddled with serious health problems, from breathing difficulties to hip dysplasia to skin allergies. A study on the breed published in Canine Genetics and Epidemiology stated, “The loss of genetic diversity and extreme changes in various regions of the genome will make it very difficult to improve breed health from within the existing gene pool.”

The study’s co-author told BBC News: “If you want to rebuild the breed, these are the building blocks you have, but they’re very few. So if you’re using the same old bricks, you’re not going to be able to build a new house.”

Ishee could be the first breeder to make brand-new bricks–if the FDA lets him–and other breeders would likely follow close behind.

As CRISPR’s costs continue to go down, interest in the technology will go up, hatching hundreds of new backyard biohackers with ideas and projects of their own. Regulatory bodies will have to walk a fine line between protecting against misuse of the technology and allowing experimentation that could benefit both animals and humans.

That experimentation could just as easily be done by our next-door neighbor as by a government agency. It’s an idea that will take some getting used to. As Ishee put it:

“When you think about genetic engineering, you think of PhDs in white coats working in multi-million-dollar labs. The idea of a dog breeder in rural Mississippi doing genetic engineering in his shed is insane. But that’s how you know you’re in the future, right?”

This article originally appeared on Singularity Hub, a publication of Singularity University.