Photo By: Petty Officer 1st Class Melissa Leake Department of Defense

By weather.com meteorologists

August 06 2020 12:50 PM EDT

weather.com

Far From Louisiana, Laura Has Brought Smelly Beaches to Florida

At a Glance

- NOAA and Colorado State University have both increased their hurricane season forecasts this week.

- NOAA’s forecast calls for 19 to 25 named storms, including 7 to 11 hurricanes.

- CSU predicts there could be 24 named storms, including 12 hurricanes.

- These forecasts include the 9 named storms and two hurricanes that have already formed this season.

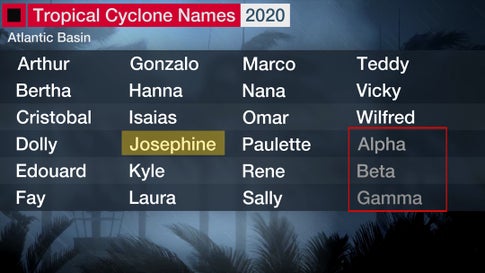

- If the forecast holds, 2020’s tropical storm and hurricane names would be used up and require use of the Greek alphabet

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, already busy through early August, could be one of the most active on record, according to two separate outlooks released this week by NOAA and Colorado State University (CSU).

NOAA’s outlook released Thursday predicts an “extremely active” season with 19 to 25 named storms, including 7 to 11 hurricanes. Three to 6 of those hurricanes could become major hurricanes — Category 3 or higher (115-plus-mph winds)on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

“This year, we expect more, stronger, and longer-lived storms than average, and our predicted ACE range extends well above NOAA’s threshold for an extremely active season,” said Gerry Bell, Ph.D., lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

The ACE index — short for Accumulated Cyclone Energy — takes into account not just the number, but also the intensity and longevity of storms and hurricanes.

CSU’s outlook released Wednesday calls for 24 named storms, 12 of which are expected to become hurricanes, and five of those hurricanes becoming major hurricanes — Category 3 or higher (115-plus-mph winds) on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

The CSU forecast is almost double the 30-year (1981-2010) average of 13 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes and is four storms, three hurricanes and one major hurricane more than its last outlook issued in early July.

If the forecast holds, 2020 would have the second most number of storms in any season, just behind 2005’s 28 storms. It would also tie both 1969 and 2010 for the second most hurricanes in any season, again trailing only 2005’s 15 hurricanes.

The CSU and NOAA outlooks include the nine named storms and two hurricanes that have already formed.

(Data: NOAA/NHC)

If the forecast number of named storms from CSU and the upper-end of the NOAA’s outlook happen, it would use up the entire list of 2020 tropical storm and hurricane names and require use of the Greek alphabet for the remaining named storms. That’s only happened once before in the record-smashing 2005 hurricane season.

During the record-breaking 2005 season, CSU’s August forecast predicted 20 named storms, 10 hurricanes and 6 major hurricanes.

Here are the factors CSU, NOAA and other seasonal forecasters are keying on for a very active season.

Trending Toward La Niña

El Niño/La Niña, the periodic warming/cooling of the equatorial eastern and central Pacific Ocean, can shift weather patterns over a period of months. Its status is always one factor that’s considered in hurricane season forecasting.

ENSO conditions are expected to remain either neutral — neither El Niño nor La Niña — or trend toward La Niña by fall.

La Niña typically corresponds with a more active hurricane season because the cooler waters of the Eastern Pacific Ocean end up causing less wind shear along with weaker low-level winds in the Caribbean Sea.

In fact, Colorado State University tropical scientist and lead author of seasonal forecasters, Phil Klotzbach, noted that July wind shear over the Caribbean Sea was second lowest in 41 years, behind only the record 2005 hurricane season’s July shear. Wind shear rips apart developing tropical cyclones and can at least disrupt or weaken active tropical storms and hurricanes.

La Niña can also enhance rising motion over the Atlantic Basin, making it easier for storms to develop.

The La Niña years of 2010 and 2011 are among several tied for the third-most-active Atlantic seasons on record. Both years had 19 named storms.

The next La Niña year, 2016, was also active, with 15 named storms that included Category 5 Hurricane Matthew and three other major hurricanes. La Niña conditions developed midway through the hyperactive and catastrophic 2017 season that produced Harvey, Irma and Maria.

Warm Ocean

One of the other ingredients that meteorologists consider in hurricane season outlooks is current sea-surface temperatures across the Atlantic Ocean.

Klotzbach noted that water temperatures between the Lesser Antilles and the west African coast in early August were the fourth warmest since the early 1980s, exceeded only by three notoriously active hurricane seasons: 2005, 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, climate models suggest that most of, if not the entire, Atlantic Basin will be warmer than average the remainder of the hurricane season.

An above-average number of tropical storms and hurricanes is more likely if temperatures in the main development region (MDR) between Africa and the Caribbean Sea are warmer than average.

Assuming other atmospheric factors are favorable, warmer waters in this MDR allow tropical waves — the formative engines that can eventually become tropical storms — to get closer to the Caribbean and the U.S.

The active West African monsoon is expected to produce both stronger tropical waves migrating west off Africa and a more conducive environment for development in the tropical Atlantic Basin in 2020, Klotzbach noted.

What Does This Mean for the United States?

While there have been nine named storms already this season, much of the hurricane season still lies ahead.

Using the ACE index mentioned earlier, there is roughly 90 percent of the hurricane season still ahead as of early August. This includes what is typically the most active stretch from late August into September.

While a higher number of named storms and hurricanes raises the odds of more landfalls, there is no strong correlation between the number of storms or hurricanes and U.S. landfalls in any given season.

One or more of the remaining named storms predicted to develop this season could hit the U.S. or none at all. That’s why residents of the coastal U.S. should prepare each year no matter the forecast.

For example, the 2010 Atlantic season tied for the second most hurricanes (12) and third most named storms (19) of any season since 1851.

Despite all those, only one tropical storm, and no hurricanes, made landfall in the mainland U.S.

Hurricane Earl made an unnerving tease of the East Coast, brushing the Outer Banks of North Carolina before recurving away. Hurricane Alex made landfall in northeast Mexico, but did bring some flooding rain into Deep South Texas.

So the season was active, but the U.S. mainland impact was relatively low, as winds steering each storm or hurricane acted to keep them largely away.

(Data: NOAA/NHC)

We’ve also seen seemingly inactive seasons deliver the one big landfall.

The 1992 hurricane season produced only seven storms. However, one of those was Hurricane Andrew, which devastated South Florida as one of only four hurricanes to landfall in the U.S. at Category 5 intensity, easily the nation’s costliest hurricane, at the time.

HURRICANE ANDREW (1992)

(Bob Epstein/FEMA)

And 1983 was even quieter than 1992.

Only four named storms — less than half the named storms already in 2020 — developed that entire season, the least of any Atlantic hurricane season since 1930.

But one of those four was Alicia.

This Category 3 hurricane pummeled the Houston metro area with high winds that shattered glass in the city’s skyscrapers, claimed 21 lives and was, itself, a billion-dollar disaster.

A hurricane season can deliver many storms but have little impact, or deliver few storms, but one or more slamming into the U.S. with major impact.

That’s why residents in the hurricane zone should prepare each year no matter what the seasonal forecast is.

The Weather Company’s primary journalistic mission is to report on breaking weather news, the environment and the importance of science to our lives. This story does not necessarily represent the position of our parent company, IBM.