Is bigger really better? – CWEB.com

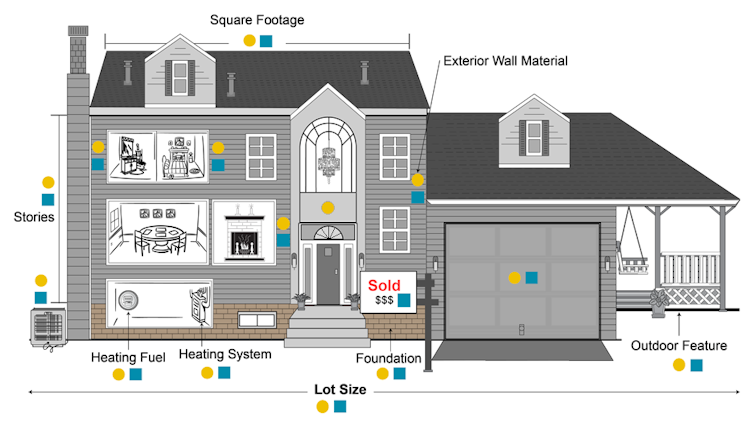

Alexandra Staub, CC BY

Alexandra Staub, Pennsylvania State University

The United States is facing a housing crisis: Affordable housing is inadequate, while luxury homes abound. Homelessness remains a persistent problem in many areas of the country.

Despite this, popular culture has often focused on housing as an opportunity for upward mobility: the American Dream wrapped within four walls and a roof. The housing industry has contributed to this belief as it has promoted ideals of “living better.” Happiness is marketed as living with both more space and more amenities.

As an architect and scholar who examines how we shape buildings and how they shape us, I’ve examined the trend toward “more is better” in housing. Opulent housing is promoted as a reward for hard work and diligence, turning housing from a basic necessity into an aspirational product.

Yet what are the ethical consequences of such aspirational dreams? Is there a point where “more is better” creates an ethical dilemma?

The better housing craze

The average single-family home built in the United States in the 1960s or before was less than 1,500 square feet in size. By 2016, the median size of a new, single-family home sold in the United States was 2,422 square feet, almost twice as large.

www.census.gov

Single-family homes built in the 1980s had a median of six rooms. By 2000, the median number of rooms was seven. What’s more, homes built in the 2000s were more likely than earlier models to have more of all types of spaces: bedrooms, bathrooms, living rooms, family rooms, dining rooms, dens, recreation rooms, utility rooms and, as the number of cars per family increased, garages.

Today, homebuilding companies promote these expanding spaces — large yards, spaces for entertainment, private swimming pools, or even home theaters — as needed for recreation and social events.

Each home a castle?

Living better is not only defined as having more space, but also as having more and newer products. Since at least the 1920s, when the “servant crisis” forced the mistress of the house to take on tasks servants had once performed, marketing efforts have suggested that increasing the range of products and amenities in our home will make housework easier and family life more pleasant. The scale of such products has only increased over time.

In the 1920s, advertising suggested that middle-class women who had once had servants to do their more odious housework could now, with the right cleaners, be able to easily do the job themselves.

By the 1950s, advertisements touted coordinated kitchens as allowing women to save time on their housework, so they could spend more time with their families. More recently, advertisers have presented the house itself as a product that will improve the family’s social standing while providing ample space for family activities and togetherness for the parent couple, all the while remaining easy to maintain. The implication has been that even if our houses get larger, we won’t need to spend more effort running them.

In my research, I note that the housework shown — cooking, doing laundry, helping children with their homework — is presented as an opportunity for social engagement or family bonding.

Advertisements never mentioned that more bathrooms also mean more toilets to scrub, or that having a large yard with a pool for the kids and their friends means hours of upkeep.

The consequences of living big

As middle-class houses have grown ever larger, two things have happened.

First, large houses do take time to maintain. An army of cleaners and other service workers, many of them working for minimal wages, are required to keep the upscale houses in order. In some ways, we have returned to the era of even middle-class households employing low-wage servants, except that today’s servants no longer live with their employers, but are deployed by firms that provide little in the way of wages or benefits.

Second, once-public spaces such as municipal pools or recreational centers, where people from diverse backgrounds used to randomly come together, have increasingly become privatized, allowing access only to carefully circumscribed groups. Even spaces that seem public are often exclusively for the use of limited populations. For example, gated communities sometimes use taxpayer funds — money that by definition should fund projects open to the public — to build amenities such as roads, parks or playgrounds that may only be used by residents of the gated community or their guests.

Limiting access to amenities has had other consequences as well. An increase in private facilities for the well-off has gone hand in hand with a reduction of public facilities available to all, with a reduced quality of life for many.

Take swimming pools. Whereas in 1950, only 2,500 U.S. families owned in-ground pools, by 1999 this number had risen to 4 million. At the same time, public municipal pools were often no longer maintained and many were shuttered, leaving low-income people nowhere to swim.

Mobility opportunities have been affected, too. For example, 65 percent of communities built in the 1960s or earlier had public transportation; by 2005, with an increase in multi-car families, this was only 32.5 percent. A reduction in public transit decreases opportunities for those who do not drive, such as youth, the elderly, or people who cannot afford a car.

Redefining the paradigm

“Living better” through purchasing bigger housing with more lavish amenities thus poses several ethical questions.

In living in the United States, how willing should we be to accept a system in which relatively opulent lifestyles are achievable to the middle class only through low-wage labor by others? And how willing should we be to accept a system in which an increase in amenities purchased by the affluent foreshadows a reduction in those amenities for the financially less endowed?

Ethically, I believe that the American Dream should not be allowed to devolve into a zero-sum game, in which one person’s gain comes at others’ loss. A solution could lie in redefining the ideal of “living better.” Instead of limiting access to space through its privatization, we could think of publicly accessible spaces and amenities as providing new freedoms though opportunities for engaging with people who are different from us and who might thus stretch our thinking about the world.

Redefining the American Dream in this way would open us to new and serendipitous experiences, as we break through the walls that surround us.

![]() Editor’s note: This piece is part of our series on ethical questions arising from everyday life. We would welcome your suggestions. Please email us at ethical.questions@theconversation.com.

Editor’s note: This piece is part of our series on ethical questions arising from everyday life. We would welcome your suggestions. Please email us at ethical.questions@theconversation.com.

Alexandra Staub, Associate Professor of Architecture; Affiliate Faculty, Rock Ethics Institute, Pennsylvania State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.