How China’s winemakers succeeded (without stealing) – CWEB.com

AP Photo/Elizabeth Dalziel

Cynthia Howson, University of Washington and Pierre Ly, University of Puget Sound

Joint ventures between Western and Chinese companies are in the news over accusations — including those of President Donald Trump — that China uses them to steal intellectual property from foreign competitors in industries like cars and technology.

Less well known, however, are the joint ventures between French and Chinese winemakers, which offer a notable counterpoint to this narrative of international rivalry — or foreign exploitation, depending on your perspective.

Unlike for cars and electronics, there are no secret technologies in the making of wine. The millennia-old fermented drink is primarily a product of the land where the grapes are grown. What differentiates the best from the rest is not proprietary technology but experience in combining agriculture, science and art.

During research visits to China’s major wine regions — from beach resorts in Shandong and Ningxia’s rocky and arid landscapes to the lush mountains of Yunnan — we encountered a blend of local and foreign winemakers, farmers, wine scientists and local government officials, all committed to establishing local wines on the world stage.

Winemaking succeeds on the back of such international collaboration. And in our experience, it’s helping Chinese wine producers overcome their biggest obstacles to success.

Cynthia Howson and Pierre Ly, Author provided

No secret technology to steal

China is currently the sixth-largest wine producer, bottling 11.4 million hectoliters in 2016, just behind Australia’s 13 million. China is fifth in terms of consumption.

A few years ago, as we explained in The Conversation, China’s wine industry was focused on overcoming the rising cost of labor, dealing with difficult climates and improving grape quality.

Now, the biggest obstacles Chinese vintners have to overcome are the country’s image problem and growing competition from foreign wine. And that’s where the foreign ventures have proven so valuable.

China has long had a reputation for counterfeiting and food safety scandals. At the same time, the wine industry has become less protected from foreign competition after bilateral trade deals with countries such as Chile and Australia eliminated some tariffs. And although there are still such barriers in place with Europe (as well as the U.S.), Chinese wine lovers still drink a ton of French wine, despite the higher prices.

Cynthia Howson and Pierre Ly, Author provided

That has meant Chinese makers of premium wines have had to raise their game to compete with skilled foreign competitors. And perhaps ironically, some of those foreign rivals have been only too happy to share knowledge and skills.

Unlike for cars, making good wine doesn’t require proprietary technology. Any serious student can learn the techniques, whether they are traditional or cutting edge, by reading, going to school or finding a mentor. Becoming a good winemaker requires experimenting with a range of tried and true methods, both in the vineyard and the cellar. There is no secret recipe, only hard work and problem solving.

Such collaborative partnerships have been essential to helping China wine producers overcome the image problem and better compete.

Cynthia Howson and Pierre Ly, Author provided

Enter the French

It might surprise readers that French Cognac producer Remy Martin was one of the first Western companies to form a joint venture in China, in this case with the city of Tianjin in 1980 to set up a winery.

The French brought winemaking skills and, in exchange, got a foot in the door into a promising market for imported Cognac. The result, Dynasty Winery, is now one of the largest Chinese wine producers.

Remy and other Western companies brought not only skills but also their brand name. Chinese wine enthusiasts — vulnerable to the same stereotypes Westerners have — might question how good a wine from an unknown domestic company might be. But if is made by a famous French wine group, whose wines they enjoy, they might give it a chance.

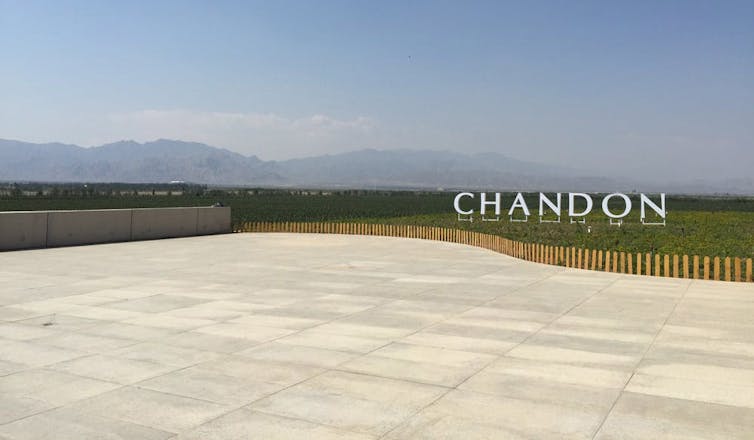

While Dynasty is a mass market brand, other more recent French-Chinese partnerships have focused on developing premium wines. One involved LVMH and a state-owned enterprise in Ningxia, a poor province often hailed as China’s most promising wine region. In 2013, the French luxury conglomerate launched Chandon China, the latest offspring in the global Chandon family of sparkling wine.

Unlike in other sectors, such as clothing or electronics, Western winemakers are not in China to take advantage of low costs. Chinese wine is expensive to make, due to the rising cost of labor, and, in some regions, the need to bury the vines to protect them from cold winters and dig them out every spring.

Moreover, you can’t outsource the production of wine to another country. Champagne can only be made in the Champagne region of France. Napa Valley wine can only be made in the Napa Valley. If a wine is made in China, it becomes Chinese wine.

Cynthia Howson and Pierre Ly

Soaring wine quality

The result, for Chinese winemakers, has been soaring quality.

Not long ago, really good Chinese wines were very hard to find. Mass market wine brands, like Changyu, Great Wall or Dynasty, were ubiquitous in supermarkets and convenience stores around the country. But most award-winning boutique wineries you read about in the media were too small or lacked marketing skills and deals with distributors that could put their wines in front of consumers.

Today the best boutique Chinese wines are far more available in major cities because the major distributors have begun to include more Chinese producers in their porfolios of primarily imported wines. This has made the best Chinese wines available in local shops frequented by wine enthusiasts, like Pudao Wines in Beijing and Shanghai, and on a few restaurant wine lists.

At a hotel restaurant in Guangzhou’s main airport in 2016, for example, we were able to order an glass of Pretty Pony, an award winning Ningxia red by Kanaan winery — something we couldn’t have done just a year earlier.

Cynthia Howson and Pierre Ly, Author provided

Next stop: exports

So how easy is it to pick up a bottle of Pretty Pony at your local supermarket if you don’t live in China?

Although exports of Chinese wine are still quite low, at just US$1.2 million in 2016 compared with $15 million for Argentina and $3.2 billion for France, a growing number of supermarkets and wine shops in Europe and the U.S. are stocking some of the best Chinese wines, from Seattle and Melbourne to London and Madrid.

![]() While it’s unlikely Chinese winemakers will be threatening their French peers anytime soon, they are now decidedly on the world’s wine map.

While it’s unlikely Chinese winemakers will be threatening their French peers anytime soon, they are now decidedly on the world’s wine map.

Cynthia Howson, Lecturer, University of Washington and Pierre Ly, Associate Professor, University of Puget Sound

This article was originally published on The Conversation.